|

| "I draw the line." |

But Jones’ cartoons are ALWAYS different than the work of the rest of the Looney Tunes directors. They hold a special significance—not only in their innovative approach to humor, but also in their bold style and abstract concepts. Jones is one of the most daring auteurs in animation; he is not constrained by animation, but finds deeper and funnier ways to find humor in the most minimalist of efforts. Friz Freleng, Robert McKimson, Tex Avery, and Bob Clampett—Jones’ superiors back when he was just a thirty-something in-betweener at Warner Bros.—were primarily gag-driven, broad in their delivery. It was hit-and-miss with their cartoons. They could either found comic-gold (i.e., Freleng’s Pink Panther and Tex Avery’s legendary pairing of Daffy Duck and Porky Pig) or comedic dullness (McKimson’s Foghorn Leghorn cartoons, which are tired, unfunny piles of abuse on a poor, hapless Southern rooster). Their styles certainly never changed throughout the half-century that they were making Looney Tunes or Merrie Melodies shorts. Frank Tashlin, the most daring of the early animators, added two key ingredient that many of the other Looney Tunes directors were missing: a frantic, Eisensteinian speed in the editing of the cartoon frames and an emphasis of artistry over humor. His Art-Deco backgrounds, new Scot-Art character designs, and appreciation of cinematic angles in his Looney Tunes cartoons had a huge influence on the budding Charles M. Jones, who struggled to find his funny niche among all of these director-veterans who made shorts before sound was ever introduced. Just for good measure, here's one of Frank Tashlin's Looney Tunes shorts from 1943, "Scrap Happy Daffy," starring Daffy Duck and Adolf Hitler (in a batty cameo):

Chuck Jones started out at Leon Schlesinger Productions—a subdivision of Warner Brothers which exclusively made cartoon-shorts—as a “inbetweener” in 1933. He was initially in charge of simply drawing the intermediate frames between two master-drawing poses of a character to provide the key illusion of movement in an era where everything you saw in a cartoon-drawn had to be hand-drawn. Jones quickly rose up the ranks of “Termite Terrace”—the affectionate name given to the ratty, small building where all of the Looney Tunes animators did their best work—and was given the prestigious position of head-director (then called “supervisor”) in 1938. His early efforts show promise but, like all his fellow freshman directors, had too much of a Disney air to them. “Naughty but Mice”—Jones’ fifth short as director—introduced a character that many of the fellow Looney Tunes directors despised: Sniffles the Mouse. His cutesy charm and gullible googly-eyed expression were not welcomed by Jones's producer Leon Schlesinger, who prided himself on separating Looney Tunes's "give-no-fucks" screwball humor from the more family-friendly, innocent Disney series. In a rare direct chat with a head-director (which, according to Freleng, he only did if was losing money), Schlesinger told Jones to either lose the Disney schtick and find his own sense of humor or hit the road.

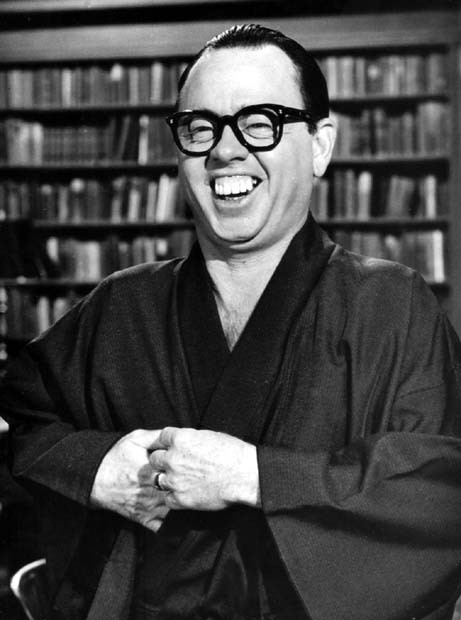

|

| Presumably Chuck's reaction to being told his ass was on-the-chopping-block. |

The story involved three college Don Juans who must save their collective fiancé from the hands of a bloodthirsty stock villain named Dan Backslide. In it, Jones introduced a revolutionary concept that would become an integral part of the Looney Tunes aesthetic: smear animation. Before it, every frame of a Looney Tunes short would be neatly hand-drawn, and the speed effect which they were then known for came from increasing the frame-rate of the final product when it was shown. But with smear animation, Jones achieved a desired effect of increasing the frantic nature of the cartoon even more than his contemporary Tashlin by asking the inbetweeners to merely smear the intermediate frames that connected the two major poses. To demonstrate, here are five separate stills from a sequence in “The Dover Boys” that show the technique in work. Note that this is a continuous sequence and that stills 3 and 5 are the “master-poses” (i.e., the boundaries that the inbetweeners must bridge together):

|

| Smear animation at work in "The Dover Boys." |

Not only did this technique make Jones’ timing crisper than any of his colleagues' cartoons, but it also signaled the first foray into the abstract animation that fascinated the young Jones. When “The Dover Boys” was released, Schlesinger and company were horrified; Chuck was hotly criticized by his own superiors for making abstract drawings that they erroneously labeled “limited animation.” What “Dover Boys” actually does is not limited animation; what "Dover Boys" employs is a manner by which the timing and speed of a cartoon may be increased, thus resulting in bigger laughs. It is artistic genius on Jones’ part—the first of many successes which he would find at Warner Bros.

When Frank Tashlin left animated cartoons for good in 1948 for directing his own live-action features, it left a gaping hole in experimentation at Looney Tunes. Jones, ever the budding intellectual, took Tashlin’s best animators and created his own Animation Dream-Team that would help him create his first bona-fide masterpieces. These included Michael Maltese as a screenwriter, Ken Harris for animation, Maurice Noble for backgrounds--and, of course, Mel Blanc and June Foray as the voices of the Looney Tunes themselves. The following year, the first of these masterpieces arrived with “Fast and Furry-Ous”, the cartoon that introduced the world to Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. The pace was Tashlinesque, the style minimalist, the humor powerful and to-the-point, the themes fatalistic in their cruel torment of the Coyote and his always-doomed-to-failed schemes to capture the Road Runner, the satire understated as the Coyote places his undying trust in the products of the suspiciously-corporate sounding ACME Corporation, and the gags elegantly crafted--all due to Jones’ astounding sense of comedic timing.

From then-on, Jones hit an artistic stride; in 1949 and for much of the 1950s, he would create some of the most recognizable, funniest products that Looney Tunes ever cranked out. Among these include the surrealist fight of animator versus creation in “Duck Amuck”, the science-fiction send-up in “Duck Dodgers in the 24th and ½ Century,” the reduction of Dick Wagner’s 5 hour opus Die Walküre into a 7-minute Bugs and Elmer short in “What’s Opera, Doc?”, and a Marxian (both Karl and Groucho) riff on the word-wars between Bugs and Daffy in the so-called “Hunting Trilogy”—three cartoons where Daffy, in his typically egotistic manner, attempts to best the much-smarter Bugs by pitting him against the hunter Elmer Fudd.

In directing his cartoons, Jones was awarded a freedom of expression unparalleled in Hollywood. His jabs at the corporate world and pop culture were cleverly masked under the guise of a Looney Tunes cartoon at a movie-house—where the kids who saw these cartoons would have these allusions sail right over their heads, and the adults would turn away their heads in blissful ignorance of the hidden realities of Jones’ work. Chuck also discovered that the subjects he was most interested in—classical music, the surreal, and thought-exercises in Sisyphean fate—were best expressed through the manic world of Looney Tunes. He single-handedly turned the studio’s ignored-star Daffy Duck into his own animated muse--an entity into which he could pour his insecurities about himself. As Jones observes:

“Bugs is confident—it shows on his face and everything about him. But Daffy is never sure because somebody may be trying to get whatever he has to his name, which is very little…I’ve never met anybody who didn’t have some of Daffy Duck in them. If somebody’s going to have the courage to become an animated director, they have to have the courage to reach down inside themselves and pull that character outside themselves and become that character. Bugs is an aspiration. Daffy is the realization. You know that that Daffy is within you; and if it’s allowed to get loose, you’d be just like him.”

“Daffy believes that everyone’s out there to do him in—which is a perfectly sound supposition, they are out to do him in. And I understand Daffy better because I was Daffy, and am Daffy. I said to myself, ‘I can dream about Bugs Bunny. But when I wake up, I’m just Daffy.’ And there’s no two ways about that.”

Jones’ work is exemplary because he pushes the Looney Tunes humor to its intellectual breaking-point. He continually asks questions on the nature of humor and personality. As "Duck Amuck” posits, does one need the physical manifestation of a character to recognize the personality that exists inside the character?

His later works “High Note” and “The Dot and the Line” try to find humor in the simplest aspects of life—the former in an unremarkable five-line musical staff, and the latter with only a circle, a straight-line, and a squiggle. The results are remarkable because Jones is able to maximize comedy in “High Note” and pathos in “The Dot and the Line” with very few elements at his disposal.

Jones is the man famous for being able to get a laugh out of a simple eyebrow-wiggle or the design of a character’s eyes; he uses the whole body to express humor, and directed the Man of a Thousand Voices, Mel Blanc, to the best voice-over work in his entire career. He does not let himself become encumbered in gag-humor, but is willing to explore the personalities of his characters. His work takes a humbling look at Daffy Duck, who is sublime in his narcissistic imperfections. Jones’ Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd are considerably different from the other Looney Tunes’ directors; they possess an intelligence and craftiness necessary to complement the slow, steady out-doing of Daffy Duck. Jones’ original characters—Sam Sheepdog and Ralph Wolf, the Coyote and the Road Runner, and Pepe Le Pew—also reflect Jones’ interest in fatalism and destiny. These are characters who are aware of their roles in a 7-minute animated cartoon and who continually attempt to change the course of their fates. But they must find out each time that they are at the mercy of the all-powerful Animator; the journey (i.e., the shorts themselves) manage to entertain us while sadly confirming their lack of power beyond the drawn page. What better example is there than the Sheepdog and Wolf cartoons of Jones’ later period—which feature the two unlikely roommates punching in a time-clock, going about a gag-filled cartoon that ends in devastation for the Wolf, and when the whistle blows, finishing the day with an amicable good-bye as they wish each other good night and “Better luck next time”?

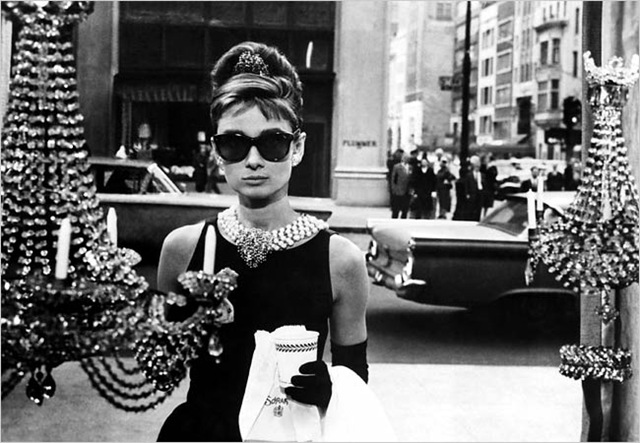

|

| Chuck Jones goes against convention by making classic enemies self-conscious actors in a jokey play-of-life. |

When Jones took over Tom and Jerry in 1963, he did not repeat the creative gag-driven bombast of the Hanna-Barbara era, but instead placed the classic cat-and-mouse duo into interesting situations which explored the nature of their on-again, off-again friendship. 1963’s “Snow-Body Loves Me” is a perfect example of this, mixing the abstract designs of his Looney Tunes best with a touching warmth that is atypical of Tom and Jerry but which, in his hands, turns into a pure pathotic moment of victory for the series. Jones gleefully bends the typical rules of an animated cartoon, giving him a chance to explore what makes a character a character.

Jones could not continue his magnificent career to the same defiant heights he took it during his classic period between 1951 and 1957. MGM, which employed Jones during most of the 1960s, closed down its animation department. He had to take on odd jobs here and there, including a memorable turn directing the classic Dr. Seuss short "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" in 1966. He gently appropriates Dr. Seuss' grotesque drawing style to suit his neat-lined approach and adds the element that distinguishes Jones cartoons from any other animators' cartoons: timing. His delicate hand is present on every frame of the special. From the transition of Mary Lou Who's apple to the Grinch's coldly red eye, to the extended long-shot that travels from Whoville to the Grinch's lair, to the slithering Grinch stealing all the contraband of the Whos down in Whoville to the tune of Thurl Ravenscroft singing the Carrollian "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch", to the intricately-drawn backgrounds of the Grinch's lair and the town of Whoville designed by his trusty collaborator Maurice Noble (who also drew the backgrounds to such Jones classics as "What's Opera, Doc?" and "Duck Dodgers in the 24th-1/2 Century"), Jones' lavish style in the Grinch special reaches, perhaps even exceeds, the expressive-artistry bar set by the best of his Looney Tunes shorts. Here's a link to the short on DailyMotion to illustrate what I'm talking about.

With 1967’s “The Bear That Wasn’t” (co-written by none other than the legendary Frank Tashlin who gave Jones the manic inspiration he needed to find his niche), a fitting end came to the Golden Era of Animation and, for the most part, to Chuck's great, unbridled stretch of winning shorts from 1939 to 1967.

He is truly one of the more underrated artists of cinema, which, in my view, is because he chose to make Looney Tunes cartoons. Lots of people assume this means they're merely for quickie viewing-pleasure and not meant to be taken seriously. It's taken on this air of pretentiousness to seriously study those Looney Tunes shorts, and people like Pauline Kael and the like will tell you they're trash and unworthy of serious academic discussion. But I do believe that Jones gives us a lot to work with in the nearly 300+ shorts he did during his long tenure at Termite Terrace, and that, yes, they are worth studying. Jones obviously makes them for kids (the core audience), but like any artist worth their salt who takes pride in what they makes, Jones's cartoons establish behind-the-scenes dialogues with other artists about how to achieve the ultimate in animated-shorts and artistic expression.

I believe what truly defines his work is his rigorous championing of other arts outside of animation. He read a lot, he talked to people and noted down their peculiarities or quirks, he listened to a lot (and I mean a lot) of music, particularly classical music and baroque. He studied the great art movements of his time, and we can see through his progression as an Looney Tunes director that he incorporates these influences in his widely-diverse oeuvre. If you notice, his earlier shorts have the air of classic 30s screwball to them; manic puns rattled off a-mile-of-minute, reminiscent of Preston Sturges's kookiest works or Hawks's Bringing Up Baby (1938). But as he grew more confident in his abilities as an artist (again, all because he studied painting, architecture, music, etc.), his short-films became much subtler, more sedate, and funnier. He learned the adage that less is more, and it works beautifully for Looney Tunes. By 1955, he could convey to an audience, through the sparse shifting of the construction-worker's eyes in the classic "One Froggy Evening," a sudden change from bemusement....

in only two frames. He is a master of suggesting the biggest emotions with the tiniest of details.

I think a lot of today's animators could take lessons from Jones on how to stop wasting precious seconds on superfluous sequences, like the establishment of these vast settings that would look boring if we saw them in live-action, and get right to the meat of the story. There's this tendency in the age of 3D cinema, that MORE IS BETTER, and that the capabilities of CGI animation must be showcased at every given opportunity in order for audiences to be invested in it. Dreamworks and Pixar aren't immune to this problem. And if there's anything Chuck Jones and his ilk show, it's that to be truly artistically superior than anybody else out there, it's always better to be minimalist. Always be on the hunt for where animation can be cut and how one can reduce a lot of talking scenes to their sparse core.

Do not let the bright colors and the frantic pace of the animated cel confuse you; behind all Jones cartoons, there is a more profound, underlying message being woven into the cartoon tapestry. His cartoons showed a man passionately in love with the cartoons—whose whole life philosophy lies embedded with his fascination in the underdogs Daffy Duck and Wile E. Coyote. As Jones himself says, “The rules are simple. Take your work, but never yourself, seriously. Pour in the love and whatever skill you have, and it will come out.”

Here's an extended list of Chuck's greatest works. The cream-of-the-crop is in astericks, the cream-of-the-crop that are my personal favorites are in bold:

- 1938—The Night Watchman

- 1939—Prest-O Change-O, Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur, Naughty but Mice, Little Lion Hunter, Sniffles and the Bookworm

- 1940—Elmer’s Candid Camera

- 1941—Elmer’s Pet Rabbit

- 1942—Conrad the Sailor, Hold the Lion Please, The Squawkin’ Hawk, *The Dover Boys at Pimento University*, My Favorite Duck, Case of the Missing Hare

- 1943—To Duck or Not to Duck, *Inky and the Minah Bird*

- 1944—Bugs Bunny and the 3 Bears, The Weakly Reporter

- 1945—Odor-Able Kitty, Trap Happy Porky, Hare Conditioned, Hare Tonic

- 1946— Hare-Raising Hare, Fair and Worm-Er

- 1947—Scent-Imental Over You, House-Hunting Mice, Little Orphan Airedale

- 1948—*You Were Never Duckier*, Haredevil Hare, Daffy Dilly, My Bunny Lies Over the Sea, Scaredy Cat

- 1949—Mississippi Hare, Mouse Wreckers, *Long-Haired Hare*, *Fast and Furry-Ous*, *For Scent-Imental Reasons*, *Rabbit Hood*

- 1950—*The Scarlet Pumpernickel*, 8-Ball Bunny, The Ducksters, Rabbit of Seville

- 1951—Scentimental Rodeo, Rabbit Fire, The Wearing of the Grin, Drip-Along Daffy

- 1952—Operation: Rabbit, Feed the Kitty, *Beep-Beep*, Going! Going! Gosh!, Rabbit Seasoning

- 1953—Don’t Give Up the Sheep, Duck Amuck, *Bully for Bugs*, *Duck Dodgers in the 24th and ½ Century*, Duck! Rabbit, Duck!

- 1954—Bewitched Bunny, Baby Buggy Bunny

- 1955—One Froggy Evening, Beanstalk Bunny, Knight-Mare Hare, Rabbit Rampage

- 1956—Broom-Stick Bunny, Gee Whiz-z-z-z-z-z-z, Rocket-Bye Baby, *Deduce, You Say!*

- 1957—Ali-Baba Bunny, What’s Opera, Doc?

- 1958—*Robin-Hood Daffy*, *Hook, Line, and Stinker!*

- 1959—Baton Bunny

- 1960—Fastest with the Mostest, High Note, Ready Woolen and Able

- 1961—The Abominable Snow-Rabbit, Compressed Hare

- 1962—A Sheep in the Deep, Martian Through Georgia

- 1963—Now Hear This, Transylvania 6-500, Pent-House Mouse

- 1964—Snow-Body Loves Me

- 1965—The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics, Tom-Ic Energy

- 1966—The Cat Above and the Mouse Below, Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

- 1967—The Bear That Wasn’t.

_NRFPT_01.jpg)